Railsのローカル変数、インスタンス変数について

Railsには変数の種類が複数あり、混乱してしまうことがあると思います。

そこで、今回は具体的なコードと表示される画面を含め、違いを確認し、つまりどういうことかの解説まで行います。

ローカル変数、インスタンス変数について、整理していきましょう。

ローカル変数とインスタンス変数の違いについて

結論からお伝えしてしまうと、ローカル変数とインスタンス変数では変数を使える範囲、スコープが違います。

posts_controller.rbのnewにて、新規投稿をしようとした例で紹介します。

インスタンス変数の例

コントローラーのコードは以下のようになっているとします。

1class PostsController < ApplicationController

2 def new

3 @post = Post.new

4 title = "ローカル変数とインスタンス変数の使い方"

5 end

6end

ローカル変数は@がついていないtitle、インスタンス変数は@がついている@postですね。

そして、ビューファイルのnew.html.erbが以下のようになっているとします。

1<%= @post %>すると、以下のように表示されます。

ぱっと見だと中身がよくわかりませんね。

ただ、何かが表示されている、エラーの赤い画面が表示されていないという事実から変数が使えていることはわかります。

ローカル変数の例

先ほどとコントローラーのコードは変えずに、ローカル変数であるtitleを表示するため、ビューファイルのコードを以下にしてみます。

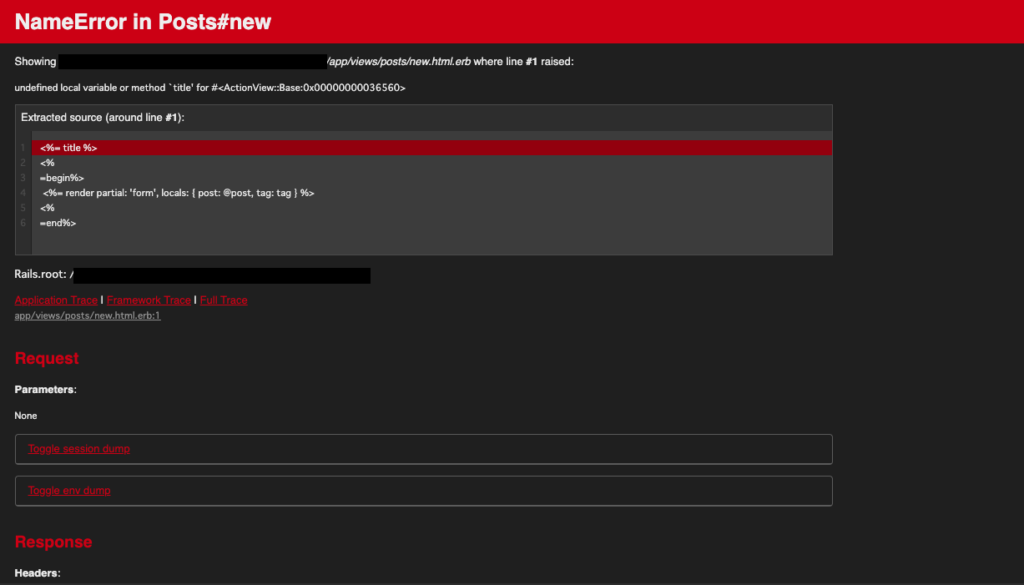

1<%= title %>すると、以下のようにエラー画面が表示されてしまいます。

今度はぱっと見うまくいっていないことがわかりますね。

なぜ使えないか、までは現時点ではわかりませんが、@をつけたインスタンス変数でないと、ビューファイルに表示ができないことがわかりました。

一応エラーの内容を読んでみると、undefind local variable ~ titleと書いてありますので、「titleというローカル変数は定義されていないよ」と言われています。

つまり、new.html.erbに定義されているtitleという変数を探しにいっているわけですね。

補足編:ローカル変数とインスタンス変数について

ここからはまだ気になることがあって、先に進めないという方に向けて、もう少し具体例を示して、解説していきます。

上記で腹落ちしたかたは作成中のアプリの作業の再開なりに戻っていただければと思います。

補足1: title変数に@をつけたら表示されるのか

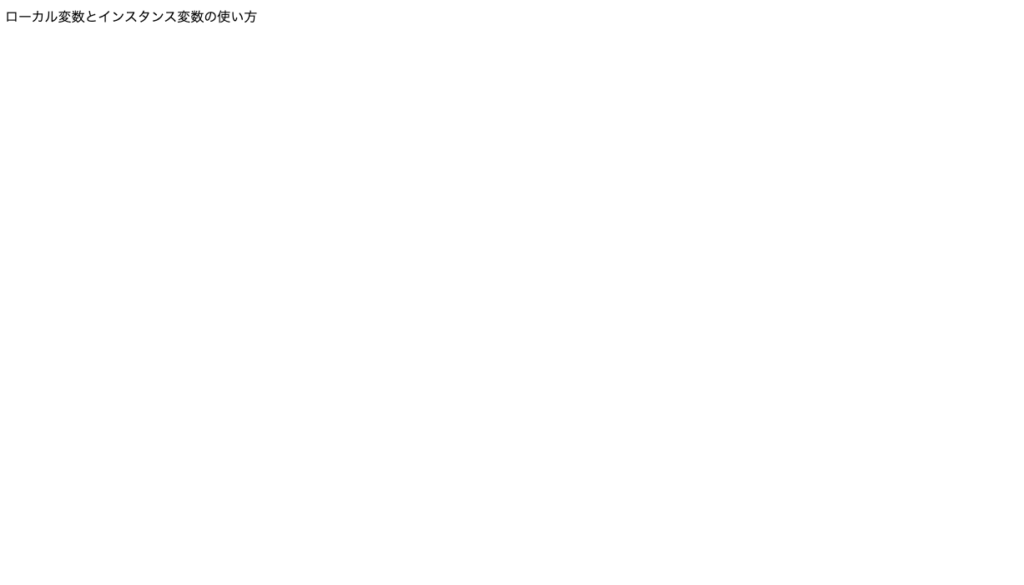

結論、表示されます。

コントローラーとビューをそれぞれ変えた実行結果までお見せします。

1class PostsController < ApplicationController

2 def new

3 @post = Post.new

4 @title = "ローカル変数とインスタンス変数の使い方"

5 end

6end1<%= @title %>

この例で、Postモデルなどテーブル(DB)に紐づいた中身のインスタンス変数でないと表示されないのではないか?という疑問に対して、「インスタンス変数の中身は関係ない」という事が証明されましたね。

補足②:@postの中身が本当にビューに渡せているのか

結論、渡せています。

しかし、先ほどの例だと、@postが本当に渡せているのか?と気になる方もいらっしゃると思うので、紹介していきます。

早速コードを変えていきたいところですが、@postはPostクラスのインスタンス変数ですので、Postモデル(テーブル)のカラムが関係します。

そのため、Postテーブルのカラムがどうなっているかを先に紹介します。

1create_table "posts", force: :cascade do |t|

2 t.string "title"

3 t.text "content"

4 t.datetime "created_at", null: false

5 t.datetime "updated_at", null: false

6 end上記のような場合で、中身が渡せているかを確認したいので、コードを以下のように変えていきます。

1class PostsController < ApplicationController

2 def new

3 @post = Post.new

4 @post.title = "タイトル"

5 title = "ローカル変数とインスタンス変数の使い方"

6 end

7end1<%= @post.title %>

補足③:@をつけないローカル変数はどこで使えるのか

結論、def ~ endの中までなら使えます。

使える範囲を小さい単位順でまとめると以下になります。

- def ~ endの中

- class ~ endの中

- 他のクラスから

rubyではブロックという単位、継承が使えますので、厳密にはもう少し細分化できますが、より混乱しますので、上記のような分け方とします。

では、実際にローカル変数はdef ~ endの中でしか使えないことを確認します。

ローカル変数がdef ~ endの中で使えるかの確認

コントローラーのコードを以下のように変更します。

1class PostsController < ApplicationController

2 def new

3 @post = Post.new

4 @post.title = "タイトル"

5 title = "ローカル変数とインスタンス変数の使い方"

6 puts title

7 endそして、Webブラウザで、「~ posts/new」にアクセスするとターミナルにtitle変数の中身、「ローカル変数とインスタンス変数の使い方」が表示されていると思います。

Started GET "/posts/new" for ::1 at 2024-03-14 09:55:24 +0900

Processing by PostsController#new as HTML

ローカル変数とインスタンス変数の使い方

Rendering layout layouts/application.html.erb

Rendering posts/new.html.erb within layouts/application

Rendered posts/new.html.erb within layouts/application (Duration: 0.1ms | Allocations: 14)

Rendered layout layouts/application.html.erb (Duration: 8.8ms | Allocations: 15323)

Completed 200 OK in 14ms (Views: 9.4ms | ActiveRecord: 0.3ms | Allocations: 20307)

これで、def ~ endの中からは使えている事がわかりました。

次に、class ~ endの中では使えるのか、を試していきます。

ローカル変数がclass ~ endの中で使えるかの確認

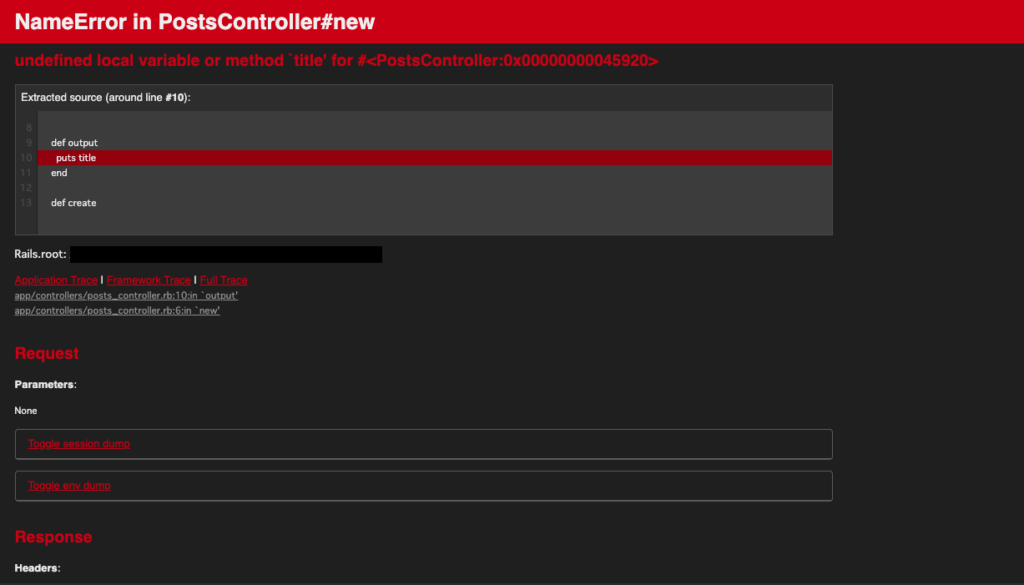

コントローラーを以下のように変更します。

1class PostsController < ApplicationController

2 def new

3 @post = Post.new

4 @post.title = "タイトル"

5 title = "ローカル変数とインスタンス変数の使い方"

6 output

7 end

8

9 def output

10 puts title

11 end

12endすると、以下のようにエラーになってしまいます。

エラー文を読むと、「titleというローカル変数が定義されていません」となっていますので、def~endの外、class~endの中でも使えない事がわかりました。

そのため、当然classの外側、つまりビューファイルからも変数は使えない事がわかります。

さらに深い補足について

ここまで読んでもよくわからない事があるという人がいると思います。

controllerからviewにはなぜ@をつけたインスタンス変数だけ渡せるのか、ということです。

回答を記述する前にRails(フレームワーク)を使う上で、初学者の方に向けて大事な心得の話をしたいと思います。

ここから先は初学者の方がどこまで何を理解するべきなのか、ということを書いています。

「今何を出来るようになりたいのか?」と問いを立てる

補足の部分まで分かったことをと分かっていないことを整理すると以下になると思います。

- コントローラーからビューに変数を渡すには@をつける必要がある

- @の変数の中身はなんでもビューに渡せる

コントローラーからビューに変数を渡すにはなぜ@が必要なのか?

整理してみたら次は、ここまでで出来るようになったことを整理したいと思います。

- コントローラーからビューに変数を渡せる

- ローカル変数を適切に使える

整理してみるといかがですか?検索した目的は達成していませんか?

検索している間に、何を理解したかったのか、の目的がわからなくなってしまうことはよくあることだと思うので、初学者の方は特に以下を行動してもらえると良いと思います。

- 検索前に何を困っているか、理解したいかをメモする

- 検索した記事を読んだ後はメモを見返し、今何が出来るようになったか?を自分に問う

学校の勉強とプログラミングの学習は違う点がたくさんありますので、最初はうまく行かなて当然だと僕は思っています。

プログラミング学習について困ったら以下から相談もしてみてください。

それでも知りたい方へ

転職されることをゴールに学習されている方は優先順位、時間の使い方を整理していただいた上で、調べる余裕があればヒントをお出ししますので、さらに自分で調べてみてください。

ここから先は記事を読んだから理解できるモノではないと思っていますので、ヒントという形にしています。

コントローラーとビューをそれぞれを深ぼる

インスタンス変数を渡す側のコントローラー、受け取る側のビューをそれぞれ深ぼる必要があります。

コントローラーはActionControllerを継承しているので、Githubから検索すると以下のコードに辿り着けます。

- コントローラーのGithub探索

-

1# frozen_string_literal: true 2 3# :markup: markdown 4 5require "action_view" 6require "action_controller/log_subscriber" 7require "action_controller/metal/params_wrapper" 8 9module ActionController 10 # # Action Controller Base 11 # 12 # Action Controllers are the core of a web request in Rails. They are made up of 13 # one or more actions that are executed on request and then either it renders a 14 # template or redirects to another action. An action is defined as a public 15 # method on the controller, which will automatically be made accessible to the 16 # web-server through Rails Routes. 17 # 18 # By default, only the ApplicationController in a Rails application inherits 19 # from `ActionController::Base`. All other controllers inherit from 20 # ApplicationController. This gives you one class to configure things such as 21 # request forgery protection and filtering of sensitive request parameters. 22 # 23 # A sample controller could look like this: 24 # 25 # class PostsController < ApplicationController 26 # def index 27 # @posts = Post.all 28 # end 29 # 30 # def create 31 # @post = Post.create params[:post] 32 # redirect_to posts_path 33 # end 34 # end 35 # 36 # Actions, by default, render a template in the `app/views` directory 37 # corresponding to the name of the controller and action after executing code in 38 # the action. For example, the `index` action of the PostsController would 39 # render the template `app/views/posts/index.html.erb` by default after 40 # populating the `@posts` instance variable. 41 # 42 # Unlike index, the create action will not render a template. After performing 43 # its main purpose (creating a new post), it initiates a redirect instead. This 44 # redirect works by returning an external `302 Moved` HTTP response that takes 45 # the user to the index action. 46 # 47 # These two methods represent the two basic action archetypes used in Action 48 # Controllers: Get-and-show and do-and-redirect. Most actions are variations on 49 # these themes. 50 # 51 # ## Requests 52 # 53 # For every request, the router determines the value of the `controller` and 54 # `action` keys. These determine which controller and action are called. The 55 # remaining request parameters, the session (if one is available), and the full 56 # request with all the HTTP headers are made available to the action through 57 # accessor methods. Then the action is performed. 58 # 59 # The full request object is available via the request accessor and is primarily 60 # used to query for HTTP headers: 61 # 62 # def server_ip 63 # location = request.env["REMOTE_ADDR"] 64 # render plain: "This server hosted at #{location}" 65 # end 66 # 67 # ## Parameters 68 # 69 # All request parameters, whether they come from a query string in the URL or 70 # form data submitted through a POST request are available through the `params` 71 # method which returns a hash. For example, an action that was performed through 72 # `/posts?category=All&limit=5` will include `{ "category" => "All", "limit" => 73 # "5" }` in `params`. 74 # 75 # It's also possible to construct multi-dimensional parameter hashes by 76 # specifying keys using brackets, such as: 77 # 78 # <input type="text" name="post[name]" value="david"> 79 # <input type="text" name="post[address]" value="hyacintvej"> 80 # 81 # A request coming from a form holding these inputs will include `{ "post" => { 82 # "name" => "david", "address" => "hyacintvej" } }`. If the address input had 83 # been named `post[address][street]`, the `params` would have included `{ "post" 84 # => { "address" => { "street" => "hyacintvej" } } }`. There's no limit to the 85 # depth of the nesting. 86 # 87 # ## Sessions 88 # 89 # Sessions allow you to store objects in between requests. This is useful for 90 # objects that are not yet ready to be persisted, such as a Signup object 91 # constructed in a multi-paged process, or objects that don't change much and 92 # are needed all the time, such as a User object for a system that requires 93 # login. The session should not be used, however, as a cache for objects where 94 # it's likely they could be changed unknowingly. It's usually too much work to 95 # keep it all synchronized -- something databases already excel at. 96 # 97 # You can place objects in the session by using the `session` method, which 98 # accesses a hash: 99 # 100 # session[:person] = Person.authenticate(user_name, password) 101 # 102 # You can retrieve it again through the same hash: 103 # 104 # "Hello #{session[:person]}" 105 # 106 # For removing objects from the session, you can either assign a single key to 107 # `nil`: 108 # 109 # # removes :person from session 110 # session[:person] = nil 111 # 112 # or you can remove the entire session with `reset_session`. 113 # 114 # By default, sessions are stored in an encrypted browser cookie (see 115 # ActionDispatch::Session::CookieStore). Thus the user will not be able to read 116 # or edit the session data. However, the user can keep a copy of the cookie even 117 # after it has expired, so you should avoid storing sensitive information in 118 # cookie-based sessions. 119 # 120 # ## Responses 121 # 122 # Each action results in a response, which holds the headers and document to be 123 # sent to the user's browser. The actual response object is generated 124 # automatically through the use of renders and redirects and requires no user 125 # intervention. 126 # 127 # ## Renders 128 # 129 # Action Controller sends content to the user by using one of five rendering 130 # methods. The most versatile and common is the rendering of a template. 131 # Included in the Action Pack is the Action View, which enables rendering of ERB 132 # templates. It's automatically configured. The controller passes objects to the 133 # view by assigning instance variables: 134 # 135 # def show 136 # @post = Post.find(params[:id]) 137 # end 138 # 139 # Which are then automatically available to the view: 140 # 141 # Title: <%= @post.title %> 142 # 143 # You don't have to rely on the automated rendering. For example, actions that 144 # could result in the rendering of different templates will use the manual 145 # rendering methods: 146 # 147 # def search 148 # @results = Search.find(params[:query]) 149 # case @results.count 150 # when 0 then render action: "no_results" 151 # when 1 then render action: "show" 152 # when 2..10 then render action: "show_many" 153 # end 154 # end 155 # 156 # Read more about writing ERB and Builder templates in ActionView::Base. 157 # 158 # ## Redirects 159 # 160 # Redirects are used to move from one action to another. For example, after a 161 # `create` action, which stores a blog entry to the database, we might like to 162 # show the user the new entry. Because we're following good DRY principles 163 # (Don't Repeat Yourself), we're going to reuse (and redirect to) a `show` 164 # action that we'll assume has already been created. The code might look like 165 # this: 166 # 167 # def create 168 # @entry = Entry.new(params[:entry]) 169 # if @entry.save 170 # # The entry was saved correctly, redirect to show 171 # redirect_to action: 'show', id: @entry.id 172 # else 173 # # things didn't go so well, do something else 174 # end 175 # end 176 # 177 # In this case, after saving our new entry to the database, the user is 178 # redirected to the `show` method, which is then executed. Note that this is an 179 # external HTTP-level redirection which will cause the browser to make a second 180 # request (a GET to the show action), and not some internal re-routing which 181 # calls both "create" and then "show" within one request. 182 # 183 # Learn more about `redirect_to` and what options you have in 184 # ActionController::Redirecting. 185 # 186 # ## Calling multiple redirects or renders 187 # 188 # An action may contain only a single render or a single redirect. Attempting to 189 # try to do either again will result in a DoubleRenderError: 190 # 191 # def do_something 192 # redirect_to action: "elsewhere" 193 # render action: "overthere" # raises DoubleRenderError 194 # end 195 # 196 # If you need to redirect on the condition of something, then be sure to add 197 # "and return" to halt execution. 198 # 199 # def do_something 200 # redirect_to(action: "elsewhere") and return if monkeys.nil? 201 # render action: "overthere" # won't be called if monkeys is nil 202 # end 203 # 204 class Base < Metal 205 abstract! 206 207 # Shortcut helper that returns all the modules included in 208 # ActionController::Base except the ones passed as arguments: 209 # 210 # class MyBaseController < ActionController::Metal 211 # ActionController::Base.without_modules(:ParamsWrapper, :Streaming).each do |left| 212 # include left 213 # end 214 # end 215 # 216 # This gives better control over what you want to exclude and makes it easier to 217 # create a bare controller class, instead of listing the modules required 218 # manually. 219 def self.without_modules(*modules) 220 modules = modules.map do |m| 221 m.is_a?(Symbol) ? ActionController.const_get(m) : m 222 end 223 224 MODULES - modules 225 end 226 227 MODULES = [ 228 AbstractController::Rendering, 229 AbstractController::Translation, 230 AbstractController::AssetPaths, 231 232 Helpers, 233 UrlFor, 234 Redirecting, 235 ActionView::Layouts, 236 Rendering, 237 Renderers::All, 238 ConditionalGet, 239 EtagWithTemplateDigest, 240 EtagWithFlash, 241 Caching, 242 MimeResponds, 243 ImplicitRender, 244 StrongParameters, 245 ParameterEncoding, 246 Cookies, 247 Flash, 248 FormBuilder, 249 RequestForgeryProtection, 250 ContentSecurityPolicy, 251 PermissionsPolicy, 252 RateLimiting, 253 AllowBrowser, 254 Streaming, 255 DataStreaming, 256 HttpAuthentication::Basic::ControllerMethods, 257 HttpAuthentication::Digest::ControllerMethods, 258 HttpAuthentication::Token::ControllerMethods, 259 DefaultHeaders, 260 Logging, 261 262 # Before callbacks should also be executed as early as possible, so also include 263 # them at the bottom. 264 AbstractController::Callbacks, 265 266 # Append rescue at the bottom to wrap as much as possible. 267 Rescue, 268 269 # Add instrumentations hooks at the bottom, to ensure they instrument all the 270 # methods properly. 271 Instrumentation, 272 273 # Params wrapper should come before instrumentation so they are properly showed 274 # in logs 275 ParamsWrapper 276 ] 277 278 MODULES.each do |mod| 279 include mod 280 end 281 setup_renderer! 282 283 # Define some internal variables that should not be propagated to the view. 284 PROTECTED_IVARS = AbstractController::Rendering::DEFAULT_PROTECTED_INSTANCE_VARIABLES + %i( 285 @_params @_response @_request @_config @_url_options @_action_has_layout @_view_context_class 286 @_view_renderer @_lookup_context @_routes @_view_runtime @_db_runtime @_helper_proxy 287 @_marked_for_same_origin_verification @_rendered_format 288 ) 289 290 def _protected_ivars 291 PROTECTED_IVARS 292 end 293 private :_protected_ivars 294 295 ActiveSupport.run_load_hooks(:action_controller_base, self) 296 ActiveSupport.run_load_hooks(:action_controller, self) 297 end 298end

また、ビュー側も同様にGithubで検索していくと、以下になります。

- ビューファイルのGithub探索

-

1# frozen_string_literal: true 2 3require "active_support/core_ext/module/attr_internal" 4require "active_support/core_ext/module/attribute_accessors" 5require "active_support/ordered_options" 6require "action_view/log_subscriber" 7require "action_view/helpers" 8require "action_view/context" 9require "action_view/template" 10require "action_view/lookup_context" 11 12module ActionView # :nodoc: 13 # = Action View \Base 14 # 15 # Action View templates can be written in several ways. 16 # If the template file has a <tt>.erb</tt> extension, then it uses the erubi[https://rubygems.org/gems/erubi] 17 # template system which can embed Ruby into an HTML document. 18 # If the template file has a <tt>.builder</tt> extension, then Jim Weirich's Builder::XmlMarkup library is used. 19 # 20 # == ERB 21 # 22 # You trigger ERB by using embeddings such as <tt><% %></tt>, <tt><% -%></tt>, and <tt><%= %></tt>. The <tt><%= %></tt> tag set is used when you want output. Consider the 23 # following loop for names: 24 # 25 # <b>Names of all the people</b> 26 # <% @people.each do |person| %> 27 # Name: <%= person.name %><br/> 28 # <% end %> 29 # 30 # The loop is set up in regular embedding tags <tt><% %></tt>, and the name is written using the output embedding tag <tt><%= %></tt>. Note that this 31 # is not just a usage suggestion. Regular output functions like print or puts won't work with ERB templates. So this would be wrong: 32 # 33 # <%# WRONG %> 34 # Hi, Mr. <% puts "Frodo" %> 35 # 36 # If you absolutely must write from within a function use +concat+. 37 # 38 # When on a line that only contains whitespaces except for the tag, <tt><% %></tt> suppresses leading and trailing whitespace, 39 # including the trailing newline. <tt><% %></tt> and <tt><%- -%></tt> are the same. 40 # Note however that <tt><%= %></tt> and <tt><%= -%></tt> are different: only the latter removes trailing whitespaces. 41 # 42 # === Using sub templates 43 # 44 # Using sub templates allows you to sidestep tedious replication and extract common display structures in shared templates. The 45 # classic example is the use of a header and footer (even though the Action Pack-way would be to use Layouts): 46 # 47 # <%= render "application/header" %> 48 # Something really specific and terrific 49 # <%= render "application/footer" %> 50 # 51 # As you see, we use the output embeddings for the render methods. The render call itself will just return a string holding the 52 # result of the rendering. The output embedding writes it to the current template. 53 # 54 # But you don't have to restrict yourself to static includes. Templates can share variables amongst themselves by using instance 55 # variables defined using the regular embedding tags. Like this: 56 # 57 # <% @page_title = "A Wonderful Hello" %> 58 # <%= render "application/header" %> 59 # 60 # Now the header can pick up on the <tt>@page_title</tt> variable and use it for outputting a title tag: 61 # 62 # <title><%= @page_title %></title> 63 # 64 # === Passing local variables to sub templates 65 # 66 # You can pass local variables to sub templates by using a hash with the variable names as keys and the objects as values: 67 # 68 # <%= render "application/header", { headline: "Welcome", person: person } %> 69 # 70 # These can now be accessed in <tt>application/header</tt> with: 71 # 72 # Headline: <%= headline %> 73 # First name: <%= person.first_name %> 74 # 75 # The local variables passed to sub templates can be accessed as a hash using the <tt>local_assigns</tt> hash. This lets you access the 76 # variables as: 77 # 78 # Headline: <%= local_assigns[:headline] %> 79 # 80 # This is useful in cases where you aren't sure if the local variable has been assigned. Alternatively, you could also use 81 # <tt>defined? headline</tt> to first check if the variable has been assigned before using it. 82 # 83 # By default, templates will accept any <tt>locals</tt> as keyword arguments. To restrict what <tt>locals</tt> a template accepts, add a <tt>locals:</tt> magic comment: 84 # 85 # <%# locals: (headline:) %> 86 # 87 # Headline: <%= headline %> 88 # 89 # In cases where the local variables are optional, declare the keyword argument with a default value: 90 # 91 # <%# locals: (headline: nil) %> 92 # 93 # <% unless headline.nil? %> 94 # Headline: <%= headline %> 95 # <% end %> 96 # 97 # Read more about strict locals in {Action View Overview}[https://guides.rubyonrails.org/action_view_overview.html#strict-locals] 98 # in the guides. 99 # 100 # === Template caching 101 # 102 # By default, \Rails will compile each template to a method in order to render it. When you alter a template, 103 # \Rails will check the file's modification time and recompile it in development mode. 104 # 105 # == Builder 106 # 107 # Builder templates are a more programmatic alternative to ERB. They are especially useful for generating XML content. An XmlMarkup object 108 # named +xml+ is automatically made available to templates with a <tt>.builder</tt> extension. 109 # 110 # Here are some basic examples: 111 # 112 # xml.em("emphasized") # => <em>emphasized</em> 113 # xml.em { xml.b("emph & bold") } # => <em><b>emph & bold</b></em> 114 # xml.a("A Link", "href" => "http://onestepback.org") # => <a href="http://onestepback.org">A Link</a> 115 # xml.target("name" => "compile", "option" => "fast") # => <target option="fast" name="compile"\> 116 # # NOTE: order of attributes is not specified. 117 # 118 # Any method with a block will be treated as an XML markup tag with nested markup in the block. For example, the following: 119 # 120 # xml.div do 121 # xml.h1(@person.name) 122 # xml.p(@person.bio) 123 # end 124 # 125 # would produce something like: 126 # 127 # <div> 128 # <h1>David Heinemeier Hansson</h1> 129 # <p>A product of Danish Design during the Winter of '79...</p> 130 # </div> 131 # 132 # Here is a full-length RSS example actually used on Basecamp: 133 # 134 # xml.rss("version" => "2.0", "xmlns:dc" => "http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/") do 135 # xml.channel do 136 # xml.title(@feed_title) 137 # xml.link(@url) 138 # xml.description "Basecamp: Recent items" 139 # xml.language "en-us" 140 # xml.ttl "40" 141 # 142 # @recent_items.each do |item| 143 # xml.item do 144 # xml.title(item_title(item)) 145 # xml.description(item_description(item)) if item_description(item) 146 # xml.pubDate(item_pubDate(item)) 147 # xml.guid(@person.firm.account.url + @recent_items.url(item)) 148 # xml.link(@person.firm.account.url + @recent_items.url(item)) 149 # 150 # xml.tag!("dc:creator", item.author_name) if item_has_creator?(item) 151 # end 152 # end 153 # end 154 # end 155 # 156 # For more information on Builder please consult the {source 157 # code}[https://github.com/jimweirich/builder]. 158 class Base 159 include Helpers, ::ERB::Util, Context 160 161 # Specify the proc used to decorate input tags that refer to attributes with errors. 162 cattr_accessor :field_error_proc, default: Proc.new { |html_tag, instance| content_tag :div, html_tag, class: "field_with_errors" } 163 164 # How to complete the streaming when an exception occurs. 165 # This is our best guess: first try to close the attribute, then the tag. 166 cattr_accessor :streaming_completion_on_exception, default: %("><script>window.location = "/500.html"</script></html>) 167 168 # Specify whether rendering within namespaced controllers should prefix 169 # the partial paths for ActiveModel objects with the namespace. 170 # (e.g., an Admin::PostsController would render @post using /admin/posts/_post.erb) 171 class_attribute :prefix_partial_path_with_controller_namespace, default: true 172 173 # Specify default_formats that can be rendered. 174 cattr_accessor :default_formats 175 176 # Specify whether submit_tag should automatically disable on click 177 cattr_accessor :automatically_disable_submit_tag, default: true 178 179 # Annotate rendered view with file names 180 cattr_accessor :annotate_rendered_view_with_filenames, default: false 181 182 class_attribute :_routes 183 class_attribute :logger 184 185 class << self 186 delegate :erb_trim_mode=, to: "ActionView::Template::Handlers::ERB" 187 188 def cache_template_loading 189 ActionView::Resolver.caching? 190 end 191 192 def cache_template_loading=(value) 193 ActionView::Resolver.caching = value 194 end 195 196 def xss_safe? # :nodoc: 197 true 198 end 199 200 def with_empty_template_cache # :nodoc: 201 subclass = Class.new(self) { 202 # We can't implement these as self.class because subclasses will 203 # share the same template cache as superclasses, so "changed?" won't work 204 # correctly. 205 define_method(:compiled_method_container) { subclass } 206 define_singleton_method(:compiled_method_container) { subclass } 207 208 def inspect 209 "#<ActionView::Base:#{'%#016x' % (object_id << 1)}>" 210 end 211 } 212 end 213 214 def changed?(other) # :nodoc: 215 compiled_method_container != other.compiled_method_container 216 end 217 end 218 219 attr_reader :view_renderer, :lookup_context 220 attr_internal :config, :assigns 221 222 delegate :formats, :formats=, :locale, :locale=, :view_paths, :view_paths=, to: :lookup_context 223 224 def assign(new_assigns) # :nodoc: 225 @_assigns = new_assigns 226 new_assigns.each { |key, value| instance_variable_set("@#{key}", value) } 227 end 228 229 # :stopdoc: 230 231 def self.empty 232 with_view_paths([]) 233 end 234 235 def self.with_view_paths(view_paths, assigns = {}, controller = nil) 236 with_context ActionView::LookupContext.new(view_paths), assigns, controller 237 end 238 239 def self.with_context(context, assigns = {}, controller = nil) 240 new context, assigns, controller 241 end 242 243 # :startdoc: 244 245 def initialize(lookup_context, assigns, controller) # :nodoc: 246 @_config = ActiveSupport::InheritableOptions.new 247 248 @lookup_context = lookup_context 249 250 @view_renderer = ActionView::Renderer.new @lookup_context 251 @current_template = nil 252 253 assign_controller(controller) 254 _prepare_context 255 256 super() 257 258 # Assigns must be called last to minimize the number of shapes 259 assign(assigns) 260 end 261 262 def _run(method, template, locals, buffer, add_to_stack: true, has_strict_locals: false, &block) 263 _old_output_buffer, _old_virtual_path, _old_template = @output_buffer, @virtual_path, @current_template 264 @current_template = template if add_to_stack 265 @output_buffer = buffer 266 267 if has_strict_locals 268 begin 269 public_send(method, buffer, **locals, &block) 270 rescue ArgumentError => argument_error 271 raise( 272 ArgumentError, 273 argument_error. 274 message. 275 gsub("unknown keyword:", "unknown local:"). 276 gsub("missing keyword:", "missing local:"). 277 gsub("no keywords accepted", "no locals accepted"). 278 concat(" for #{@current_template.short_identifier}") 279 ) 280 end 281 else 282 public_send(method, locals, buffer, &block) 283 end 284 ensure 285 @output_buffer, @virtual_path, @current_template = _old_output_buffer, _old_virtual_path, _old_template 286 end 287 288 def compiled_method_container 289 raise NotImplementedError, <<~msg.squish 290 Subclasses of ActionView::Base must implement `compiled_method_container` 291 or use the class method `with_empty_template_cache` for constructing 292 an ActionView::Base subclass that has an empty cache. 293 msg 294 end 295 296 def in_rendering_context(options) 297 old_view_renderer = @view_renderer 298 old_lookup_context = @lookup_context 299 300 if !lookup_context.html_fallback_for_js && options[:formats] 301 formats = Array(options[:formats]) 302 if formats == [:js] 303 formats << :html 304 end 305 @lookup_context = lookup_context.with_prepended_formats(formats) 306 @view_renderer = ActionView::Renderer.new @lookup_context 307 end 308 309 yield @view_renderer 310 ensure 311 @view_renderer = old_view_renderer 312 @lookup_context = old_lookup_context 313 end 314 315 ActiveSupport.run_load_hooks(:action_view, self) 316 end 317end

ここからさらに探索的に別のファイル、コードを読む必要がありますので、気になった方はぜひこれらのヒントをもとにコードを深ぼってください。

まとめ

コントローラーとビューを具体例にローカル変数とインスタンス変数の違いを確認していきました。

- ローカル変数はdef ~ endの中でしか使えない

- インスタンス変数はコントローラー→ビューなど他のクラスでも使える

プログラミングについて聞いてみたい事がある方は以下から、質問をしてみてください。